6.270

Contest

The Name

Strategy

Design

Results

Analysis

Pictures

Code

The Team

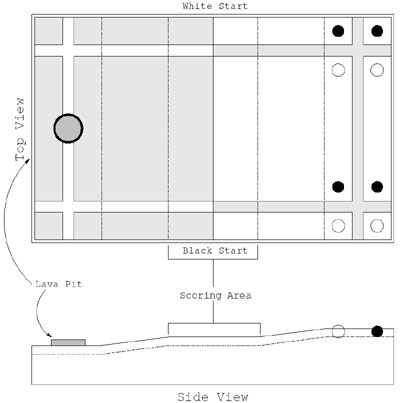

The Contest

6.270 is a robotics contest held at MIT every January. The goal of 6.270 is to teach students about robotic design by giving them the hardware, software, and information they need to design, build, and program their own robots. Each team is given a kit valued at $1500 which includes LEGOs, a handyboard, and various other electronic components.This year's (2003) competition, "Montezuma's Revenge," involves a three-tiered playing field. Robots are placed at the designated starting positions and try to collect balls of their own color. If they manage to bring one of their balls to rest at the center plateau, they get 1 point. If they manage to place the ball inside the bucket on the lower plateau, they are awarded 4 points. Each round lasts for 60 seconds and at the end of the round, the team with the highest score wins.

The Playing Field

The Name

We had a hard time thinking of a name for our robot because it went through so many different revisions. Since our robot's final design looked kind of like a steam shovel, we thought of naming our robot "Constructicon", after the powerful 5-component Decepticon in the anime "Transformers." However, one day in lab, somebody started playing "kerpal - kick dog.mp3", the infamous prank call that has been floating around the Internet for years. Unable to think of a better name, we decided to pay homage to the popular mp3 and named our robot "kerpal".Strategy

Our robot went for an "all-or-nothing" type strategy. We decided that since the bin at the bottom of the playing field was the jackpot, we should go for it. If we manage to score into the bucket, the best our opponent can do is tie us with 4 points. We designed our robot to line follow up the hill to collect a ball. If we get the enemy's ball dump it and try again. When we get our own ball, our robot will then line-follow down the hill, turn toward the center of the field, and then proceed to dump our ball into the bin.Our Robot's Design

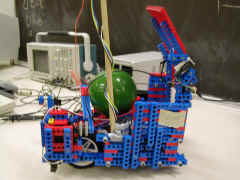

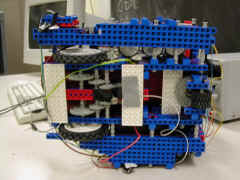

Our robot went through at least 6 different revisions before settling at its final design. We wanted our robot to be able to line follow, so we placed 5 sensors on the bottom (5 LED/phototransistor pairs). Our robot has two back wheels, each driven by a motor. It also has a third, un-driven front wheel that is connected to a servo to help with steering and balance. The gear train running the back wheels has a 45:1 gear ratio, which we thought would give our robot a very quick speed.Originally, we rested our handyboard and batteries on a roof on top of the robot, but our bot turned out to be too top-heavy. We fixed the problem by building a compartment on the left side of the robot that could hold the handyboard snugly and a compartment on the right side of the robot that could hold the batteries.

The front of our robot was what gave us the most trouble. Originally, we wanted a row of spinning tires hanging above a ramp that would knock balls in. That didn't work very well, because the motor that was attached to the overhanging arm holding the axle of tires made the arm bounce vigorously. We had difficulty finding a way to gear down the motor, and we also started running into the problem of having our robot not fit into the size constraints. After playing around with several configurations of the tires, we decided to discard the idea and try a new one. We finally settled on a steam-shovel like design that incorporated a long arm/ramp powered by a servo. The servo itself was powerful enough to lift the ramp arm, but unfortunately it turned out that one servo was not enough to also lift a ball. If the ramp had another servo or motor helping it lift the arm, then it might actually have been powerful enough to lift a ball. Alternatively, we could have tried gearing down the servo to sacrifice the servo's 180-degree swivel range to a 90-degree range with twice the power. Unfortunately, we ran out of time and could not implement a fix.

Had our robot been able to lift a ball, we had a color sensor on the ramp itself that would detect whether or not a collected ball was one of ours or one of the enemy's. The entire back half of our robot is a downward slope so that a ball can roll down the back and into a bucket. We had a servo-powered back gate that would swivel up and down depending on whether we wanted to keep a ball or dump it.

Results

In Round 1, our team went up against Team 40, "Cortez the Killer." Cortez was designed to go up the hill and grab all 4 balls on its side, hoping to get a double-win for both teams in the event that their opponent doesn't score. Unfortunately for them, they grabbed more of our balls than they did theirs, and our team actually ended up having the 3rd-highest score out of all 60 teams in the round. Unfortunately, our beacon failed to turn on in the beginning of the round and we were given a loss via disqualification.Final Analysis

The main problem that plagued our robot was the one described earlier concerning a weak ramp. Essentially, we overestimated the power that a servo was able to provide.Another problem that our robot had was that after we had finished construction on the robot, we noticed that it seemed to run out of power sometimes as it tried to turn and climb up the hills. This is probably due to the 45:1 gear ratio that we employed. Originally, we had thought that a 45:1 ratio would give our robot a fast speed. However, we underestimated exactly how heavy the robot would turn out to be. Furthermore, because we moved our handyboard and batteries from the top of the robot to the side compartments, the weights were no longer centered over our main gear train. I believe we could have fixed this issue by using a gear ratio of 75:1 or 90:1, trading in speed for power.

Pictures

|

|

|

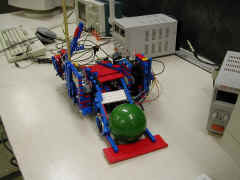

A contest ball resting comfortably on the ramp. |

A side view of kerpal. The ramp is in its starting, upwards position, while the ball is held in place by the back gate. |

|

|

|

|

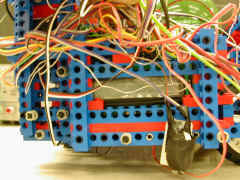

The handyboard compartment on the left side of kerpal was made to be able to accommodate all the wires and also be able to show the LCD display. |

The underside of kerpal is exposed. The gear train employs a 45:1 gear ratio. |

Code

persistent.lis

-- Loads the below two files consecutively

persistent.c

-- Sets up persistent variables

robot2.c -- The

meat of our code

The Team

Team 9 consists of David Tsai '05 and Min Zhang '05.

Andy Lin '05 was also originally part of the team, but

stopped coming to class after the 4th day of IAP.